Common Symptoms of a Pinched Nerve

Understanding pinched nerve symptoms begins with recognizing the sensations that often signal nerve compression. This overview explains common signs in a clear and approachable way, offering general awareness without suggesting diagnoses or treatment promises.

Nerve compression can significantly impact daily activities and quality of life. Recognizing the warning signs early allows for timely intervention and prevents potential complications. The symptoms vary depending on the location and severity of the compression, but certain patterns emerge across different cases.

Early Signs of a Pinched Nerve

The initial indicators of nerve compression often develop gradually. Many people first notice a tingling sensation or pins-and-needles feeling in the affected area. This sensation, medically termed paresthesia, typically occurs in the hands, feet, arms, or legs. Numbness may accompany or follow the tingling, creating a sensation of reduced feeling in specific regions.

Pain represents another early warning sign. The discomfort may feel sharp and shooting or present as a dull, persistent ache. Some individuals describe a burning sensation radiating along the nerve pathway. These symptoms often worsen during certain movements or positions, particularly those that increase pressure on the compressed nerve. Nighttime symptoms are common, as sleeping positions may inadvertently aggravate the compression.

Weakness in the affected muscles can develop as the condition progresses. Individuals may notice difficulty gripping objects, reduced coordination, or a feeling that the affected limb is not responding as expected. These early signs should prompt evaluation, as prolonged nerve compression can lead to more serious complications.

Common Causes of Nerve Compression

Several factors contribute to the development of pinched nerves. Repetitive motions represent a significant risk factor, particularly in occupational settings. Activities that require prolonged periods of bending, reaching, or maintaining awkward positions can gradually increase pressure on nerves. Assembly line work, computer use with poor ergonomics, and certain athletic activities create environments conducive to nerve compression.

Structural issues within the body also play a role. Herniated or bulging discs in the spine can press against nerve roots, causing symptoms that radiate into the limbs. Bone spurs, which are bony projections that develop along bone edges, may narrow the spaces through which nerves travel. Arthritis contributes to nerve compression by causing inflammation and structural changes in joints.

Obesity increases the risk of developing pinched nerves by adding extra weight and pressure to nerve pathways. Pregnancy can temporarily cause nerve compression due to fluid retention and weight gain. Injuries from accidents, falls, or sports activities may result in swelling or structural damage that compresses nearby nerves. Certain medical conditions, including diabetes and thyroid disorders, make nerves more susceptible to compression.

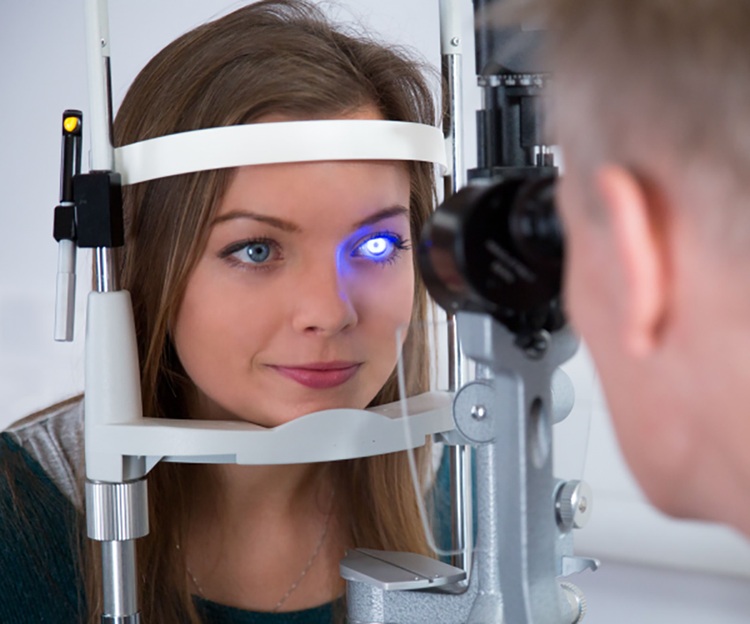

How Doctors Diagnose Pinched Nerves

Medical professionals employ multiple approaches to accurately diagnose nerve compression. The diagnostic process typically begins with a comprehensive medical history and physical examination. Physicians ask detailed questions about symptom onset, location, duration, and factors that worsen or improve the condition. They inquire about occupational activities, recent injuries, and existing medical conditions.

During the physical examination, doctors assess muscle strength, reflexes, and sensation in the affected areas. They may perform specific tests that reproduce symptoms by placing the nerve under tension or pressure. Observing how symptoms respond to different positions and movements provides valuable diagnostic information.

Imaging studies help visualize the structures surrounding the nerve. X-rays reveal bone abnormalities, such as fractures, arthritis, or bone spurs. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides detailed images of soft tissues, including discs, ligaments, and nerves themselves. Computed tomography (CT) scans may be used when MRI is not suitable.

Electrodiagnostic tests measure electrical activity in nerves and muscles. Nerve conduction studies assess how quickly electrical signals travel through nerves, helping identify areas of compression or damage. Electromyography (EMG) evaluates the electrical activity of muscles, revealing whether nerve compression has affected muscle function. These tests provide objective data that confirms the diagnosis and assesses severity.

Blood tests may be ordered to rule out underlying conditions that contribute to nerve problems, such as diabetes, vitamin deficiencies, or thyroid dysfunction. The combination of clinical evaluation and diagnostic testing enables physicians to develop targeted treatment plans.

Treatment Approaches and Management

Treatment strategies vary based on the location and severity of nerve compression. Conservative approaches form the first line of treatment for most cases. Rest allows inflamed tissues to heal and reduces pressure on the affected nerve. Modifying activities that aggravate symptoms prevents further damage.

Physical therapy plays a central role in recovery. Therapists design exercise programs that strengthen supporting muscles, improve flexibility, and promote proper posture. Stretching exercises reduce tension on compressed nerves. Manual therapy techniques may help restore normal movement patterns.

Medications manage pain and inflammation. Over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) reduce swelling and discomfort. Prescription medications, including corticosteroids and muscle relaxants, may be necessary for more severe cases. Some individuals benefit from corticosteroid injections directly into the affected area.

Orthotics and braces provide support and limit movements that compress nerves. Wrist splints help with carpal tunnel syndrome, while cervical collars may be used temporarily for neck-related nerve compression. These devices allow healing while maintaining some functional ability.

Surgical intervention becomes necessary when conservative treatments fail or when nerve compression causes progressive weakness or loss of function. Procedures aim to remove the source of pressure, whether it involves removing a herniated disc portion, widening nerve pathways, or addressing bone spurs. Recovery times vary depending on the specific procedure and individual factors.

Prevention and Long-Term Outlook

Preventing nerve compression involves maintaining healthy lifestyle habits and ergonomic practices. Regular exercise strengthens muscles that support proper posture and joint alignment. Maintaining a healthy weight reduces unnecessary pressure on nerves throughout the body.

Workplace ergonomics deserve attention. Adjusting desk height, computer monitor position, and chair support can significantly reduce the risk of developing nerve compression. Taking regular breaks from repetitive activities allows tissues to recover. Proper lifting techniques protect the spine and associated nerves.

The prognosis for pinched nerves is generally favorable when addressed promptly. Many individuals experience complete resolution of symptoms with conservative treatment. Early intervention prevents permanent nerve damage and preserves full function. However, ignoring symptoms or delaying treatment can lead to chronic pain and lasting neurological deficits.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.