What Happens in the Body When Beta Thalassemia Is Present

Beta thalassemia is a blood-related condition that affects how the body produces hemoglobin, and this article introduces its basics in a clear and approachable way. The overview helps readers understand what the condition is, why it occurs, and how it may influence overall health. The goal is to offer a calm, informative starting point without overwhelming details, setting the tone for a straightforward explanation.

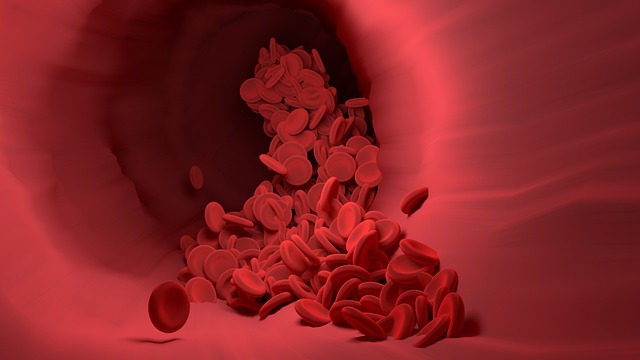

Beta thalassemia represents one of the most common inherited blood disorders worldwide, particularly affecting populations from Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, Asian, and African ancestries. This condition fundamentally alters how red blood cells function, creating a ripple effect throughout the entire body that can manifest in various ways depending on the severity of the genetic mutation.

Understanding the Basics of Beta Thalassemia

Beta thalassemia occurs when genetic mutations prevent the body from producing sufficient beta-globin chains, which are essential components of hemoglobin. Hemoglobin consists of four protein chains: two alpha and two beta. When beta chains are deficient or absent, the balance is disrupted, leading to abnormal red blood cell formation. Individuals inherit beta thalassemia genes from their parents, and the condition follows an autosomal recessive pattern. If both parents carry the trait, their children have a 25 percent chance of inheriting the disease. The genetic mutations can vary significantly, resulting in different forms of the condition including thalassemia minor, intermedia, and major, each with distinct physiological impacts on the body.

How Beta Thalassemia Affects the Body

When beta thalassemia is present, the body struggles to maintain adequate oxygen delivery to tissues and organs. The deficiency in normal hemoglobin production leads to chronic anemia, where red blood cells are fewer in number, smaller in size, and less capable of transporting oxygen efficiently. This oxygen deprivation triggers compensatory mechanisms throughout the body. The bone marrow attempts to increase red blood cell production, often expanding significantly and causing skeletal deformities, particularly in the facial bones and skull. The spleen and liver enlarge as they work overtime to filter out defective red blood cells, a process that can lead to organ dysfunction over time. Additionally, iron overload becomes a significant concern, either from repeated blood transfusions or from increased intestinal iron absorption that occurs when ineffective red blood cell production is present.

Understanding Beta Thalassemia and Its Effects

The effects of beta thalassemia extend far beyond simple anemia. Patients often experience profound fatigue and weakness due to insufficient oxygen reaching muscles and tissues. Growth and development may be delayed in children, as the body diverts resources to compensate for the blood disorder. Bone health becomes compromised due to marrow expansion and potential iron deposits, increasing fracture risk. The cardiovascular system faces additional stress as the heart must work harder to pump oxygen-poor blood throughout the body, potentially leading to cardiac complications including arrhythmias and heart failure if left unmanaged. The endocrine system can also be affected, with patients experiencing complications such as diabetes, thyroid disorders, and delayed puberty due to iron accumulation in glands. Immune function may be compromised, particularly in individuals who have undergone splenectomy, making them more susceptible to infections.

Cellular Changes and Red Blood Cell Production

At the cellular level, beta thalassemia creates a hostile environment for red blood cells. The imbalance between alpha and beta chains causes excess alpha chains to accumulate within developing red blood cells. These unpaired alpha chains form toxic aggregates that damage cell membranes, leading to premature destruction of red blood cells both within the bone marrow and in circulation. This process, called ineffective erythropoiesis, means that many red blood cells die before they can mature and enter the bloodstream. The surviving red blood cells often have abnormal shapes and reduced lifespan, typically surviving only 10 to 20 days compared to the normal 120 days. The body responds by accelerating red blood cell production, but this compensatory mechanism cannot keep pace with the destruction rate, resulting in persistent anemia.

Long-Term Complications and Organ Systems

Over time, the chronic nature of beta thalassemia affects virtually every organ system. Iron overload, whether from transfusions or increased absorption, deposits in the heart, liver, and endocrine glands, causing progressive damage. Liver cirrhosis can develop from both iron accumulation and chronic hepatitis infections acquired through transfusions. Cardiac complications represent one of the leading causes of mortality in thalassemia patients, as iron deposits interfere with heart muscle function and electrical conduction. Bone density decreases due to marrow expansion and hormonal imbalances, leading to osteoporosis and increased fracture risk. The gallbladder frequently develops stones due to increased bilirubin production from red blood cell breakdown. Skin pigmentation changes occur as iron accumulates in tissues, giving a bronze or gray appearance.

Physiological Adaptations and Body Responses

The body employs various adaptive mechanisms when beta thalassemia is present. Blood vessels may dilate to improve oxygen delivery to tissues despite reduced oxygen-carrying capacity. The kidneys increase production of erythropoietin, a hormone that stimulates red blood cell production, though this response proves inadequate given the underlying genetic defect. Metabolic rate may increase as the body attempts to compensate for reduced oxygen availability. The immune system becomes activated due to chronic inflammation from red blood cell destruction, potentially contributing to additional complications. These adaptive responses, while intended to maintain homeostasis, often contribute to the overall disease burden and complications experienced by individuals with beta thalassemia.

Conclusion

Beta thalassemia creates profound changes throughout the body, affecting red blood cell production, oxygen delivery, and multiple organ systems. The genetic defect in beta-globin chain production sets off a cascade of physiological responses that impact bone marrow, spleen, liver, heart, endocrine glands, and skeletal structure. Understanding these bodily changes helps explain the varied symptoms patients experience and underscores the importance of comprehensive medical management. While the condition presents significant challenges, advances in treatment approaches continue to improve outcomes and quality of life for individuals living with beta thalassemia.